by István Pávai

Early Source Material

Although the first scattered references to Hungarian folk music tradition were not written for the purposes of scientific record, they are all the more significant for the paucity of information left to posterity from the deep past: the farther back one looks, the fewer sources on the subjects of music and dance one finds.

Some of the earliest extant fragments of information on the singing of folk songs come from the broader legend of Saint Gerard, Bishop of Csanád, whose age produced literary works, visual depictions, prohibitions, sermons, judicial documents, and travelogues that witness to the nature of some forms of contemporary music and dance.

Of course, the methodical study of such early sources was not begun until after the rise of modern folk scholarship. Nevertheless, the use of works of literature, fine art, and folk art – even 20th century works – is justified, subject to an appropriate degree of caution, as numerous past writers, artists, and folk artists have recorded scenes and events from folk life with due accuracy and attention to detail.

A second major group of sources from times prior to the advent of research in the modern sense originates with collecting work conducted in conjunction with the “discovery” of folklore itself.

The Romantic Era

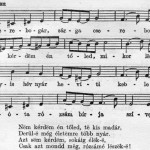

In the mid-19th century, before any well-defined concept of folk music had emerged, most collections consisted primarily of works of art music and folk-style, urban art songs (photo: Cserebogár-nóta, or May Bug Song, a piece representative of urban art songs of the 19th century). Such music was disseminated throughout the nation via a phenomenon known as “folk theatre” and by the activity of the hotel and restaurant owners who employed urban Roma musicians. It was under the influence of the latter that contemporary language began referring to Hungarian folk-style art music as “Gypsy music,” which led to the general misunderstanding to which even Franz Liszt famously subscribed. Eventually, Roma artists on foreign tour spread this erroneous notion to Western Europe, where it persists to some extent even today. For their part, urban Roma musicians did not identify musically with – nor were, in fact, even familiar with – the true musical folklore of rural Roma communities, striving rather to assimilate the traits of Hungary’s urban middle classes. For this reason, the music they played can actually be regarded as belonging to neither Roma, nor Hungarian folklore.

In addition to the folk-style art songs that by this time enjoyed popularity on a national scale, 19th-century collections did include some authentic Hungarian folk songs, though not always in accurately notated form. The first tentative attempts at the actual scientific study of these came with the work of Gábor Mátray (1797-1875) and István Bartalus (1821-1899), who recognised the significance of melodic and textual variation across different regions, and who first proposed the idea of comprehensive publication. At the end of the century, Áron Kiss (1845 – 1908) published his collection of children’s game songs, which, unlike the artificial educational songs released to contemporary nursery schools from central sources, sought to compile and disseminate musical material from the world of musical games played by children in rural Hungarian communities. It is no coincidence, therefore, that the collection was regarded by Bartók as the greatest publication of the 19th century.

Scientific Accuracy: Collecting by Phonograph

The real breakthrough came just prior to the turn of the century with the work of Béla Vikár, who, lacking the training of a musician, was the first in Europe to apply the phonograph to the collection of folk songs. It was the beginning of the age of machine recording, which, through precise repeatability, allowed for the accurate notation of technical minutiae, in-depth study of performance style, and preservation of related information for posterity. In his publications, Vikár concentrated on the poetry inherent in folk song lyrics, leaving the melodies to be sketched out by István Kereszty and later transcribed in meticulous detail by Béla Bartók. Following in Vikár’s footsteps, János Seprődi (1874-1923), too, began using the phonograph in his own fieldwork in Transylvania. It is important to note that without the technique of machine recording, instrumental folk music, with its great variety and virtuoso playing style, would have been impossible to transcribe accurately.

The Science of Ethnomusicology: Zoltán Kodály and Béla Bartók

In 1903, Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) commenced study of the body of songs recorded by Vikár on phonograph cylinder. Later, in 1905, he and Béla Bartók made their first attempts at the methodical, comprehensive collection of folk music from every territory where Hungarian was spoken. It was the beginning of the true scientific study of Hungarian folk music, and the results it soon brought were to enrich the field of international comparative musicology.

The significance of the pentatonic scale to Hungarian folk music was first posited in conjunction with Kodály’s studies in Northern Hungary and Bartók’s fieldwork in eastern Transylvania, leading to the examination of a possible eastern connection among the Finno-Ugric and Turkic peoples of the Volga River region. Bartók extended his own research to include first Hungary’s Romanian, Slovakian, and Serbian neighbours, and later, even more distant peoples (Turks and Arabs), while Kodály broke ground in his exploration of eastern relationships and the comparison of Hungarian folk music to known historical melodies.

The Interwar Period

The redrawing of national borders following World War I, which attached the more archaic peripheral Hungarian-speaking territories to other countries, made continued fieldwork in these areas considerably more difficult. It was at this time that Bartók published his first comprehensive analysis and scientific overview of Hungarian folk songs (A magyar népdal, 1924), which categorised melodies as old, new, or mixed in style, and which divided up the territory of study on the basis of musical dialect.

Dialects of Hungarian Folk Music

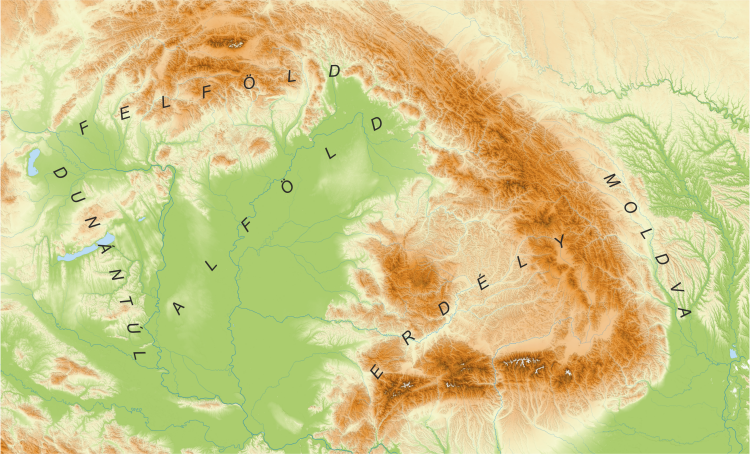

Dialects of Hungarian Folk Music

Dunántúl (Transdanubia), Felföld (Upland), Alföld (Great Plain), Erdély (Transylvania), Moldva (Moldavia)

Bartók’s work was followed several decades later by Kodály’s own overview of Hungarian folk music (A magyar népzene, 1937), which demonstrated eastern influences through melodic comparison, and used historic parallels to explore the presence of European melodies in Hungary during the medieval and modern eras. During the interwar period, significant progress was made in exploring the music of the Moldavian Csángó people, whose archaic culture represented the easternmost Hungarian-speaking ethnic group (Pál Domokos Péter, Gábor Lükő, Sándor Veress, Péter Balla), and a series of gramophone records of Hungarian folk music (known as the “Pátria Recordings”) was also produced. With the gramophone, the greater part of the body of known folk songs could be made accessible to the public in mass-produced form using a more perfect technology than that of the phonograph.

László Lajtha and the Lajtha Group

In the early 1940s, with the re-annexation of northern Transylvania and southern Slovakia to Hungary, researchers again turned their attention toward peripheral territories, giving rise to the first monographs on individual villages and folk musical instruments.

The study of instrumental music, in particular, picked up momentum through the invention of the gramophone and, later, the reel-to-reel tape recorder (magnetophone), which enabled the preservation and study of more complex music consisting of multiple parts. The leading figure in this pursuit was László Lajtha, who also played a groundbreaking role in the study of folk dance music during the 1940s and 1950s.

In addition to these topics, the Lajtha research group also commenced work on such previously neglected genres as vernacular sacred song and apocryphal prayer. One of Lajtha’s former colleagues, Benjamin Rajeczky, earned his laurels with the study of the relationship between folk music and the Gregorian chant, and the publication of the first series of folk music recordings on LP (microgroove).

Lajos Vargyas

The 1950s witnessed the achievements of prominent ethnomusicologist Lajos Vargyas (1914-2007), who drafted a compendium of musical examples to accompany the comprehensive work of Zoltán Kodály; discovered a set of melodies related to the Ob-Ugric music studied by Bence Szabolcsi; explored the relationships between French and Hungarian folk music; completed an exhaustive comparative study of European ballads that included musical aspects of the genre; authored a new overview of Hungarian folk music; and made substantial progress in the analysis of Hungarian folk poetry from a musical perspective.

Folk Music Research Outside Hungary

During the 1950s, collecting efforts among peoples living outside the Hungarian national borders began to pick up and gain institutional support. Important results were achieved in Romania, for example, by a group headed by János Jagamas, whose students, István Almási, Zoltán Kallós, and Ilona Szenik, went on to make further significant contributions in their individual work. Prominent researchers in this area during the second half of the 20th century include Tibor Ág and Margit Méry in Upper Hungary, and Anikó Bodor in the regions south of Hungary.

Systematisation and Publication

The greatest undertaking in the field of Hungarian folk music research since the Second World War is undoubtedly the comprehensive publication project first suggested by Kodály and Bartók in 1913 known as the Magyar Népzene Tára (Latin: Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae; English: Encyclopaedia of Hungarian Folk Music). In 1934, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences finally gave Bartók the means to begin preparatory work on the project by systematising folk tunes based on musicological considerations (Bartók system). After Bartók departed for the United States in 1940, the endeavour passed to Kodály, who replaced Bartók’s style-based rhythmic system with a modified version of the Ilmari Krohn cadence system (Kodály system). The first five volumes of the encyclopaedia contain tunes linked to various special occasions, most of which exhibit their own unique musical character. A key role in developing a system of musical organisation for these was undertaken by Pál Járdányi, who also worked out a new system for classifying strophic folk songs not associated with special occasions based on the relationship between the registers in which sequential lines of melody were performed.

With Kodály’s agreement, preparatory work on the publication of strophic tunes according to the Járdányi system was begun. To date, the first five volumes, by type, have been issued, while others are still in the process of publication. Later, a system of classification that organised melodies based on the simultaneous evaluation of a variety of criteria was developed independently by László Dobszay and Janka Szendrei. For the publication of new-style folk songs, a similarly individual system of organisation was developed by János Bereczky. Work has also begun on the publication of the entire Bartók system, now a closed chapter in the history of science, with all material already available on the Internet.

Other Fields of Inquiry

Naturally, Hungarian ethnomusicology has encompassed far more than the mere collection, notation, classification, and publication of Hungarian folk music. Though a complete list of research topics would overstep the limits of the present overview, a few projects are mentioned here for reason of sheer scope. László Vikár’s fieldwork studying and publishing the music of the Finno-Ugric and Turkic peoples of the Volga River, for example, spanned several decades, while Bálint Sárosi is credited with the systematic exploration and description of folk instruments and the study of instrumental folk music, a discipline that has since been taken up by an entirely new generation of researchers. Hungarian ethnomusicology was first pursued institutionally by the Ethnography Department of the Budapest Museum of Ethnography, but was later taken over by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Ethnomusicology Group, founded by Zoltán Kodály. This latter body was incorporated into the academy’s Institute for Musicology in 1974.